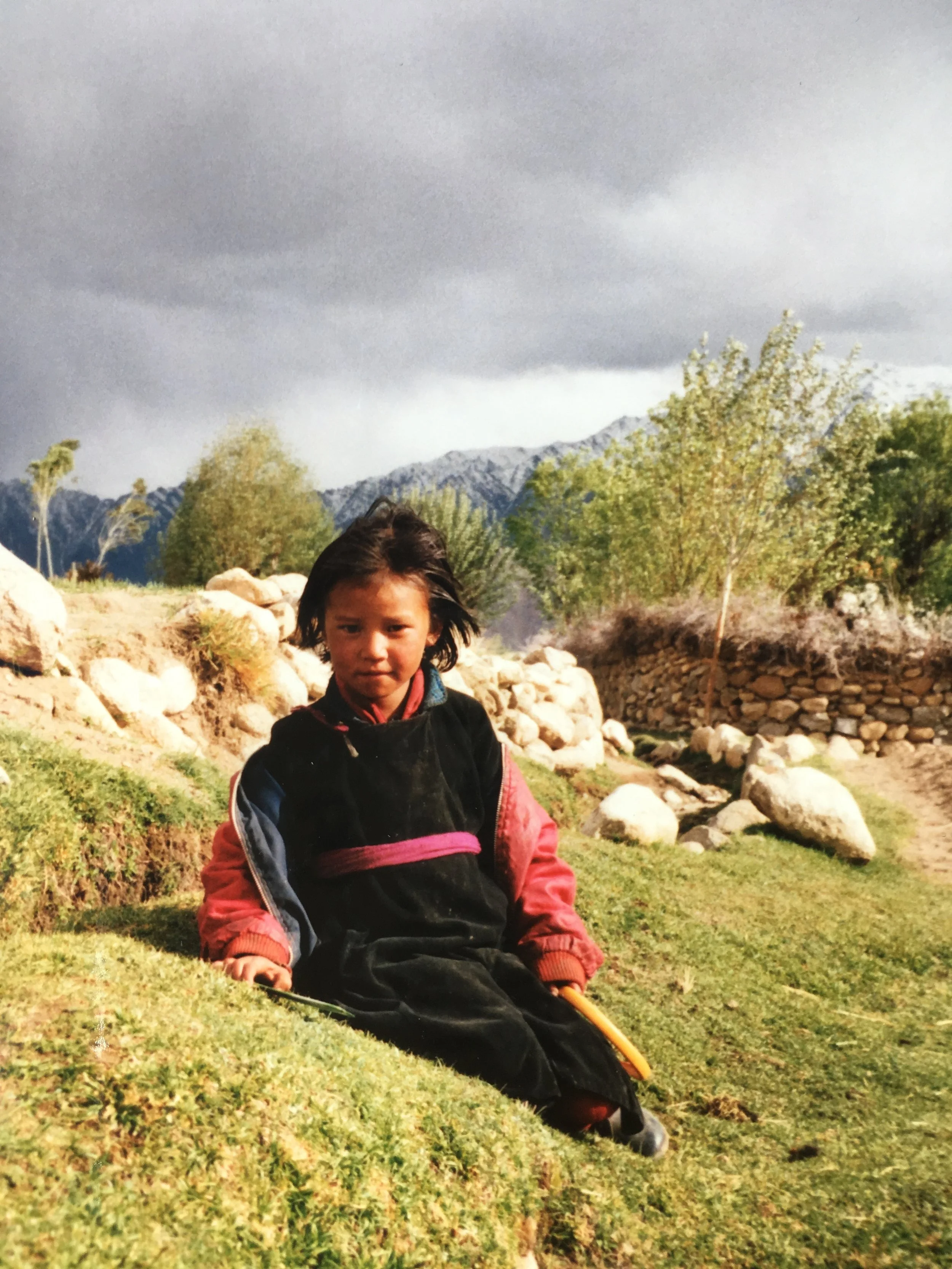

Within a resource-scarce environment, the Ladakhis live materially rich, spiritually healthy, sustainable lifestyles. Given the overuse of the term, sustainable means, “in a way that can be continued indefinitely.” In direct contrast, Americans inhabit a vast, resource-rich territory, yet many are impoverished, many others are spiritually bankrupt (to wit—they are immune to the human suffering and environmental destruction caused by their way of life), and are psychologically impaired (as evidenced, among many measures, by their heavy reliance on drugs, legal and otherwise). Often referred to as the world’s wealthiest country, it is also one of the world’s least sustainable.

Image from https://marketingland.com.

The question of lifestyle is fundamental to the human predicament. For, leaving the sanity of Ladakhi society and coming back to our world again, we must at least accept the insanity of our position. That faced with problems of geological proportion—both in extent and time, problems of our own making—we insist on business as usual, of the insanity of “doing the same thing over and again and expecting different results.” Given the evidence—a dwindling of finite resources, a potential biospheric mass extinction, a heating Earth, alongside the specter of rising populations, hunger, material inequality, and suffering—a simple tweaking of our system seems hardly sufficient. As we have seen in previous posts, the solutions that we have insisted on employing are simply revved up versions of the problems themselves, and are therefore amplifying the problems and accelerating our predicament. Economic growth, we realize, is just another way of saying growing consumption. Same with the lowering of fertility promised by the Demographic Transition: adults focus on careers and material-based lifestyles rather than on the traditional lifestyles grounded in large multi-generational families. And the technologies that we have employed—no matter how honorable our intentions may have been—have usually led to blowback, which has resulted in further consumption of mostly useless and superfluous objects and an accelerated deterioration of the environment. Our consumption continues to reduce mineral and biological reserves and unravel the biospheric weave; it further pollutes the Earth; and it places billions of people in a position where they must—indeed, their hunger has them longing to—work long hours in mind-numbing jobs.

Image: https://commonground.ca/the-real-message-in-bottle/

And yet, even with all this effort and all its environmental and existential blowback, we still cannot—as a species—provide the minimum basic material needs for all our human family. Nearly a billion people are hungry, and billions suffer the health and social consequences of micronutrient deficiencies, non-potable water, and unsanitary conditions. Nearly two billion people are without electricity.[i] All our enormous destruction of the planet has, at best, raised half of our human family to some modicum of physical comfort for some brief period, which may extend to but a few generations. And most of those who “enjoy” these minimal comforts find themselves working long hours in monotonous jobs—in Third World factories and in First World offices—with little financial security. They are born into societies where the bonds and security of family and community have become thin and tenuous. And they find themselves powerless to alter their circumstances. Their ancestors had more control over nature herself than we do over our economic and political environment.

Image: Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post.

Even in the United States, once considered the paragon of democracy, ninety percent of Americans don’t trust their government’s ability to address the relevant issues. Ninety percent of Americans believe that genetically engineered foods should be so labeled; 88% think that solar power should be developed and utilized; 90% believe that the gifting of Congressmen by registered lobbyists should be prohibited.[ii] Yet, for these three simple, sensible, significant, and relatively inexpensive initiatives there is as yet no concerted effort by the nation’s elected representatives.[iii] How less likely is it that this nation and the loosely related societies making our global civilization will be able to resolve the more complex problems of a population explosion, of global hunger, global warming, resource depletion, etc.? We have become, as the writer Daniel Quinn noted, “captives of a civilizational system that more or less compels… [us] to go on destroying the world in order to live.”[iv]

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/05/americans-strongly-favor-expanding-solar-power-to-help-address-costs-and-environmental-concerns/

Fittingly, we can admire the Ladakhis for their environmentally friendly ways. We can envy their communalism and their ability to integrate their spiritual lives with their everyday material existence. Many of us living in the psycho-spiritual wreckage of the post-industrial world feel that we are missing a meaningful relationship with the land, life, and community, and we are educated enough to sense that their absence was the bargain made for the material comforts and excitement provided by industrialization and urbanization. Still, few of us are willing to blithely annul the bargain. If given the chance, few of us would trade positions with the Ladakhis. Even if we could dissolve the strangeness by perhaps beaming ourselves into their world with the full complement of our community—our family, friends, and acquaintances, our language, our location—few of us would be willing to live with the medical ignorance, the limited diet, the infrequent baths, poor hygiene, the limits on individualism, and the provincial simplicity and ignorance of the accelerating world beyond our boundaries. From our standpoint, the Ladakhis appear to be living anachronisms. Yet, we can appreciate their virtues and might like to bring these forward into our future, to take the best of what we have learned as a species during our sojourn here, to integrate the benefits of science, for example, with the wisdom of living happily within our environmental means. What will it take to actually to do so? What will motivate us?

Image: http://ingervandyke.com/2014/05/tribal-people-western-monoculture/

ENDNOTES

[i] Rifkin (2009:510) The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis. Jermey P. Tarcher/Penguin, New York.

[ii] Solar and wind power—ABC News/Washington Post Poll, April 14-17, 2011, available at http://www.pollingreport.com/energy.htm. Accessed April 21, 2011. Lobbyist—ABC News/Washington Post Poll (Jan. 5-8, 2006). Available at http://www.citizen.org/congress/article_redirect.cfm?ID=14945. Accessed April 21, 2011.

[iii] In 2016, the U.S. congress passed a toothless bill requiring the labeling of GMOs. Lugo, D. (2016, July 8) U.S. Senate passes GMO food labeling bill. Science. doi:10.1126/science.aag0649. Accessed November 11, 2018 at https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/07/us-senate-passes-gm-food-labeling-bill.

Charles, D. (2016, July 14) Congress Just Passed a GMO Labeling Bill. Nobody’s Super Happy About It. National Public Radio (NPR). Accessed November 11, 2018 at https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/07/14/486060866/congress-just-passed-a-gmo-labeling-bill-nobodys-super-happy-about-it.

[iv] Quinn (1995:25). Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit, Bantam, New York.