Independent voices have and still do exist, of course, especially in the less expensive media such as the small press and online. And through a dizzying array of online platforms and social media outlets, the world’s citizens can and do talk to each other directly in billions of daily exchanges. But as Gonzalez and Torres submit: “…it’s not simply the right to speak, but the right to be heard by others” that is the measure of a free media.[i] An independent blog may have a thousand hits; a network website like The New York Times or Fox News will have millions of viewers. Any whispers of wisdom will be drowned out in the white-noise roar of the corporate media.

Powered by the juice of “cheap” fossil fuels, capitalism has generated a wire and wireless environment of electronic media that brings information to over half the world’s population. Radio, television, phones, and the internet surround the world’s least impoverished billions like the very air we breathe. It is so cheap, so ubiquitous, that it is almost as invisible as the air, and cheaper and materially less toxic than the water we drink and the food that we eat. And it is advertising, of course, that funds this ubiquity.

Advertisements work at all scales of society, at all levels of culture. Most conspicuously, advertising is designed to sell products. The utility and social value of the product is immaterial. Indeed, there may well be an inverse relationship to value and advertising space—far more money on hair products and beer, for example, than on exercise and broccoli. It is not about selling products that are good for people, society, or the Earth. It is not about selling what people need. It about selling whatever sells. By trying to sell products that people do not need (and indeed may be happier without), the advertising industry encourages, according to ad director Chris Hooper, “every sophomoric… irresponsible hedonistic, egotistical, narcissistic behavior.”[ii] Going just slightly deeper, it does this by skillfully exploiting our psychological proclivities. With steadfast devotion, advertisers trigger feelings of dissatisfaction in their audience—with themselves and with their possessions. In this consumer atmosphere, people “equate self-worth with ownership of goods.”[iii] As the sociologist William Catton put it, advertising is a “want-multiplying industry” that “augments human frustration.”[iv]

On another level, advertisement creates and sustains the paradigm of consumption and, by drowning out or muting every other voice, marginalizes other possible worldviews. It accomplishes this by every means available, including the powers of ubiquity and propaganda.[v] Ubiquity is accomplished through iteration, saturation, branding, product placement, and so forth, so that a person in a post-industrial society finds no respite from advertising in her waking hours. The economist Ezra J. Mishan said, “the sheer weight of reiteration rather than the power of reason influences the attitude of the public.”[vi] The average American—should there actually be such a creature—receives three thousand daily advertising messages from all the various media.[vii] About three hundred of those come from the television: that is, three hundred prolonged sales pitches.[viii] Americans spend about a year of their lives watching television commercials. Those ads come mostly in three-to-seven minute barrages between fifteen minute programming spaces. Advertising continues during the actual program, of course, with such practices as product placement and news tickers (crawlers) and floating icons on the bottom third of the screen. And there are some networks—such as the Home Shopping Network and MTV, to mention a couple of the earliest ones—where the program is advertisement; that is, the audience tunes in to explicitly watch advertisement, whether the product is a kitchen knife or a downloaded song.

And now ever more powerfully, the online medium is perfecting the art of perpetual advertisement. Through the screen comes a relentless assault of ads. Often, to even view the desired online material, one must first engage with the ad which overlays it. Concurrently, the screen’s edges are alive in ads of various schemes. The online screen is becoming more like a video game, perhaps oddly reflecting the urban world at large, where ads move about constantly on taxis, busses, trains, walls, billboards, bus stops, shop windows, screens, and even the clothes of passersby. This reflection works as two facing mirrors might, so that the origin of the image is lost in our mindspace. But again, the difference may be that with the computer screen, this virtual world is experienced mostly alone.

Given this saturation of consumerist image and text, the actual content in the media becomes irrelevant. As Marshall McLuhan stressed, the medium—not the content—is the message.[ix] So, it has become rather immaterial whether, for example, the New York Times has articles about poverty, hunger, inequality, the atrocities of war, the population explosion, global warming, corporate malfeasance, and the general biospheric breakdown. It doesn’t even really seem to matter what its position is on any of these subjects, except for perhaps how it may affect readership numbers. Advertisements fill half its paper; and, from the online version, ads radiate from the screen as the glitziest, most colorful and kinetic spaces. The advertisements (and most of content, really) reinforce the dominant consumption paradigm and the culture of collapse, and so they easily drown out any content that may be contrary to that paradigm. The audience is consumer. All else in us has been marginalized—citizen, lover, parent, worker, intellect, artist, naturalist, friend.

We can verify this at the neural level, as well. Connections between neurons are made as a response to stimuli. More iterations of a specific stimuli strengthen the neural connection.[x] Constant iteration of reward in the pleasure centers creates a person habituated to those stimuli that created the pleasant feeling. If consumption is tied to the pleasure response, to levels of the pleasure and reward hormones—dopamine, particularly—then consumption has been selected for as the default mode of pleasure satiation.[xi] Like a drug dealer, business has done its job—another consumer has been fixed. And the culture of collapse has been reinforced.

Every car driven, shirt and shoe worn, piece of gum chewed, and discarded water bottle is an advertisement for both the product and for the lifestyle of consumption in general. More subtly, the presence of one thing implies the absence of the other. IPhone instead of Droid; new instead of old; television instead of family dinner; mall instead of forest; porn instead of intimacy; consumption instead of contentment. As McLuhan found, the media technology doesn’t simply transmit information; it changes our worldview. Television doesn’t simply transmit facts and fiction, truth and lies, information about global warming and entrepreneurial heroes like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs; its ripple effects spread out at every level and scale, psychologically, socially, economically, environmentally. Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore noted, for example, in the medium is the MASSAGE: “Your family circle has widened. The worldpool of information fathered by electronic media—movies, Telstar [satellites], flight—far surpasses any possible influence mom and dad can now bring to bear. Character no longer is shaped by only two earnest, fumbling experts. Now all the world’s a sage.”[xii] And with the Internet, it takes a global village to raise a child. Sadly, a significant part of that global village that coaches, educates, and advises your teenage child is made not of wise elders but of same-aged children on Facebook, Instagram and other social networks. Much of the rest is composed of adults who are trying to get something from your child through advertisements, banal to insidious entertainment, and twitter and press releases presented as news items. As the propaganda pioneer Edward Bernays knew almost one hundred years ago, “We are governed, our minds molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.”[xiii]

The message of consumerism and the culture of collapse drowns out any other point of view. It is ubiquitous and reiterated on every transmittable frequency and piece of paper and moveable surface. And so, despite its promise as a medium of hope, as the propaganda arm for the coming biospheric consciousness, the media is presently one of the greatest obstacles to societal transformation.

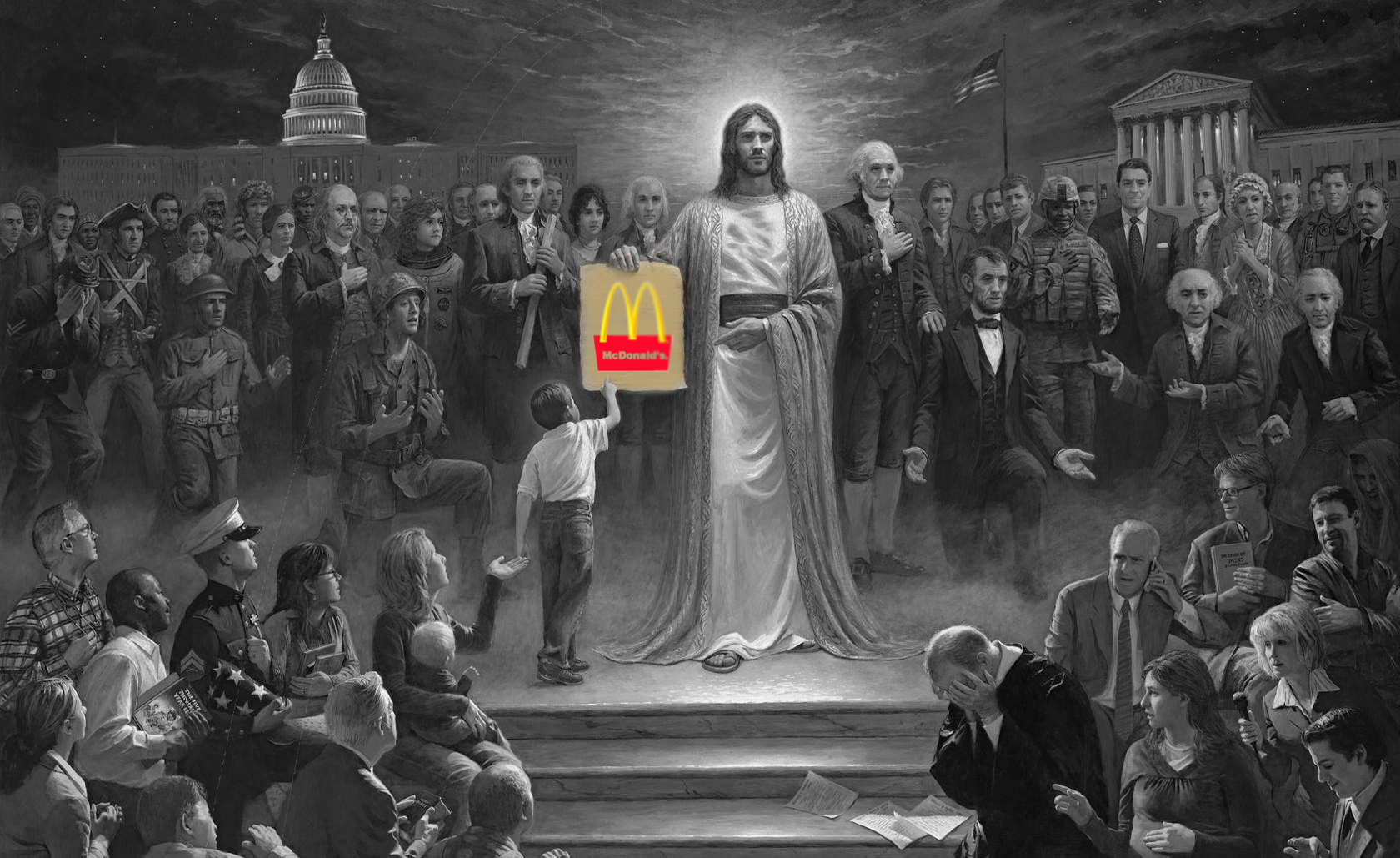

Amir Noor, Artist. https://amizle.wordpress.com/tag/consumerism-2/

REFERENCES

[i] Gonzalez, J., and Torres, J. (2011:11) News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media. Verso, London.

[ii] Cited in Bakan, J. (2005:125-126) The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, Free Press, New York.

[iii] Laszlo, E. (2006) The Chaos Point: The World at the Crossroads. Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc., Charlottesville, VA.

[iv] Catton, W.R. (1982:235) Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change, Univ. Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago.

[v] Greif, M. (2007, December 30) The Hard Sell, New York Times.

[vi] Mishan, E.J. (1993:13) The Costs of Economic Growth, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT.

[vii] Brower, M. and Leon, Warren (1999) The Consumer’s Guide to Effective Environmental Choices: Practical Advice from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Three Rivers Press, New York.

[viii] Myers, N. (1997) Consumption: Challenge to Sustainable Development, Science, v. 276, pp. 53-55.

[ix] McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill, New York.

[x] Purves, D., Augustine, G.J., Fitzpatrick, D., Katz, L.C., LaMantia, A-S., McNamara, J.O. (Editors) (1997) Neuroscience, Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers, Sunderland, MA.

[xi] Berridge, K.C. and Kringelbach, M.L. (2008) Affective Neuroscience of Pleasure: reward in Humans and Animals, Journal of Psychopharmacology, v. 199(3) pp. 457-480.

[xii] McLuhan, M. and Fiore, Q. (1967/2001:14) the medium is the MASSAGE. Gingko Press, Corte Madera, CA.

[xiii] Bernays, E. (1928/2004:37) Propaganda, Ig, Brooklyn, NY.