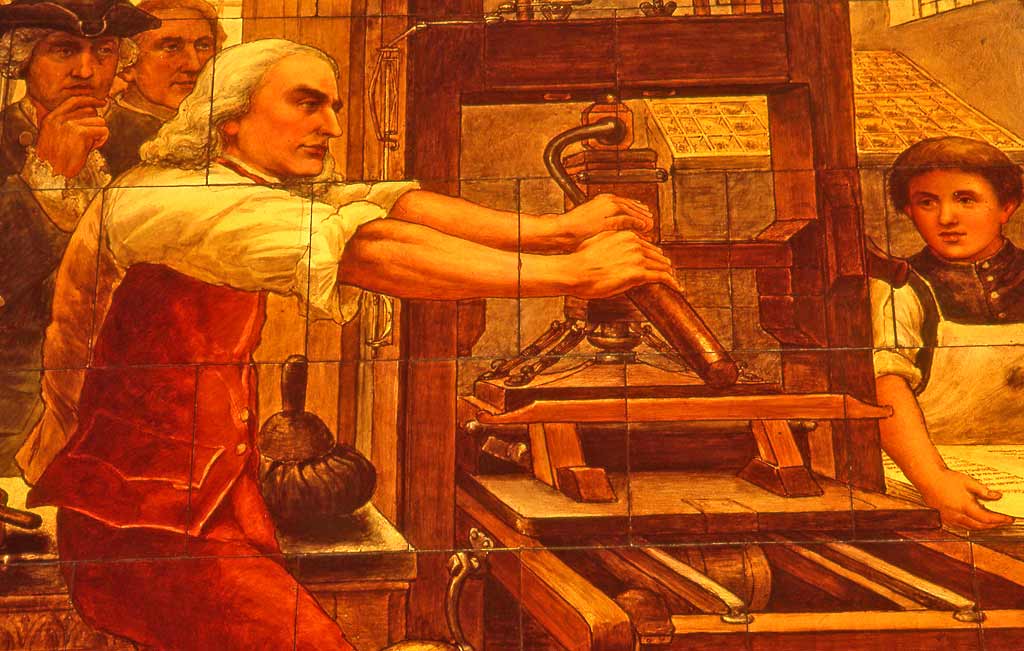

Integral as media has been to Civilization and to the culture of collapse, the media as an institution is a relative newcomer. For most of history, the heralds, scribes, academics, and artists served their masters and patrons. Rarely were they an independent voice with a novel, radical, or dissident perspective.[1] However, during the European power struggles of the 1600s—bourgeoisie versus the feudal powers of nobility and church, and later monarchy versus nobility—journalists served as mouthpieces for the competitors, and the media became a force to be reckoned with.[2] Napoleon’s famous quip, “Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets…” speaks to the emerging power of the media in the late 18th century. At about the same time in the American colonies, de Tocqueville and James Madison observed the importance of the press in self-governance. “Because its public service responsibility” was seen to be, “… so intertwined with the health of democracy itself, the press is the only business explicitly protected by the Constitution.”[3] Even then, though, the media was still largely a public sphere of opinion and alleged facts.[4] Literate people with the power of the moveable type spoke their minds and sold papers. And the medium was still, in the historian Carroll Quigley’s words, an instrument of (an albeit elite), society more than a viable self-serving institution.

It took the Industrial Revolution to institutionalize the media. This transformation involved three interrelated forces that had been evolving through the past centuries and reified in the late 18th century.[5] One, advances in printing technology and transportation allowed for the inexpensive mass production and distribution of the local newspaper. Two, a growing literate and energetic bourgeoisie created a large audience with an appetite for information and luxury goods. And three, advertising of those luxury goods paid for larger papers with more content, and eventually for investigative reporting, fact checkers, and other duties that were not simply opinion and promotion.[6] The press continued to inform and editorialize on social matters as it had for centuries, but now it was assimilated into the capitalist economy, set up to sell products.

What advertising had given the media with one hand—greater resources to inform and persuade—it took with the other—namely, independence. Through advertising, business pays for three-quarters of a newspaper’s revenue.[7] By the 21st century, newspapers were placing over forty billion dollars in ads a year in the United States, alone. Expenditures for total advertisements in all the U.S. media total more than $250 billion annually.[8] World totals for advertisement lie somewhere between five and eight hundred billion dollars annually.[9] This does not take into account the money involved in labor and production of advertisements, only their placement. The media cannot function without advertisement. Witness the crash of the newspaper business in this century as advertising dollars have been relocating to the Internet.[10] Through the sheer power of money, the media is beholden to business. It does not have the independence to speak candidly about or on issues that may alienate advertisers and audiences.

Thus the Discovery Channel’s omission of any reference to the causes for global warming during their seven-week series Frozen Planet in 2012.[11] In the last episode, On Thin Ice, spectacular images of ice calving from glaciers and ice shelves, melting ice sheets, stranded polar bears, and the disappearing Adelie penguin demonstrates with frightening force that, as narrator Richard Attenborough says, “The ends of the earth are changing.” The poles are warming ten times faster than the rest of the earth, we are told. But any discussion of human causes, carbon emissions, industrialization, consumerism, etc., was absent. It was noted, however, that less polar ice will provide new opportunities for energy exploitation and commercial shipping. In what is otherwise a stunning example of the documentary power of television, a tour de force of artistic and technical collaboration, there is an odd silence about the human influence. Vanessa Berlowitz, the series producer, admitted that they did not want to alienate their audience.[12] The organization’s judgment is not being questioned here. Far from it. In their discretion, they very well may have reached a larger audience and done far more good than had the show been candid and then been canceled for lack of funding. The main point here is that the business institution dominates the American culture and thus greatly influences the content and expression of the media about the most important issues concerning us. The 20th century propaganda of Goebbels and Stalin was crude, opaque and short-lived in comparison to that of today’s elite.

Media’s institutional fidelity to the other institutions of power is a phenomenon that is difficult to quantify. However, given the magnitude of the ecological and economic crises and the enormity of the human inequality and suffering, the relative silence on these matters speaks loudly about the institutional paradigm. That is, just as it has since the beginnings of civilization, the media is serving the interests of the powerful minority.

How critical could the media ever be about consumerism and the culture of collapse when its existence wholly depends on it? More, how critical can the media be when they are no longer distinguishable from the other institutions? Like the others, the media are peopled with millions of intelligent, well-intentioned staff. And just as in the other institutions, the successful ones, those who climb up the ladder to be lead reporters and editors, are those who are both competent and who generally accept the institutional belief system. Note that even the best and the brightest—the enlightened opinion writers for the New York Times, for example, such as the liberal Paul Krugman and the independent thinker Thomas Friedman are, despite their incisive critiques, major proponents of capitalism, the media, and American “democracy.” Chomsky writes that there “is a kind of filtering device which ends up with people who really honestly (they aren’t lying) internalize the framework of belief and attitudes of the surrounding power system in the society… They wouldn’t be there unless they had already demonstrated that nobody has to tell them what to write because they are going to say the right thing. If they had started off at the Metro desk or something, and had pursued the wrong kind of stories, they never would have made it to the positions where they can now say anything they like.”[13] In The Death and Life of American Journalism, Robert McChesney and John Nichols write, “The [corporate] pressure is applied subtly; more often than not, successful editors and reporters tend to internalize the necessary values so no pressure is necessary.”[14] And of course they know what the expected values are, as the media elites are part of the very same social networks as are members the other four principal institutions: same neighborhoods, same places of worship, same parties, same schools, same sources of information, same set of beliefs.

Journalists in Geneva. UN Photo/Violaine Martin

In this neighborhood pool, information waves are reflected back and forth, reinforced by constant reiteration and a delusional sense that the sources are independent. A few examples will suffice to make the point.

- Since most organizations within the television, radio, and other electronic media cannot (competitively) afford to hire independent on-the-scenes reporters, they gather their information from other media, mainly newspapers.[15]

- And newspaper houses have greatly cut their staff in the past decade. Many of the major newspapers are going bankrupt.[16]

- Which means the information pool is getting even smaller. So, how good is the newspapers’ information? “A 1990 study found that almost 40 percent of the news content in a typical U.S. newspaper originated from public-relations press releases, story, memos, and suggestions.”[17]

- “According to the Columbia Journalism Review, more than half of the Wall Streets Journal’s news stories are based solely on press releases.”[18]

- Press releases are simply propaganda pieces released by interested parties to the media. In the United States there are more people employed in public relations to manipulate news and public opinion and policy than there are news reporters. By 2008, there were three-fold more.[19]

· News organizations tend to be owned by multi-billion dollar corporations (as of this writing, Disney owns ABC, ESPN, Pixar, and much more; General Electric owns MSNBC; Time Warner owns Turner Broadcasting Network, Warner Brothers, Time Inc., HBO and many others), or they are multi-billion dollar transnational mass media conglomerates (NBC-Universal-Telemundo (which is owned by Comcast and General Electric), Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp (which includes Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, and Twentieth Century Fox, among many others). Or they enjoy a complex, ever changing legal relationship, as is the case with the giants CBS, Viacom, and Westinghouse.[20]

Independence of large media businesses, if it ever existed at all, disappeared early in the institution’s history. The tipping point for the press began in the 1960s, when the major newspaper companies left their family and small company origins and became publicly traded companies.[21] Among them were the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Times-Mirror.[22] In 2009, revenues for the New York Times Company was $2.4 billion (down from $3.4 billion in 2005): besides publishing The New York Times, the Boston Globe and the International Herald Tribune, it owns about twenty regional papers and maintains significant ownership in other businesses such as the Boston Red Sox Baseball Club.[23] By most counts, as one scholar put it, “Since the mid-1980s the corporations that produce news in the United States have begun to treat it less as a public trust and more as a commodity, simply a product for sale.”[24]

Fittingly, the electronics media belies its image of informational democracy by concentrating the power of worldview into even fewer hands than the print media.[25] Radio and television have enjoyed little democracy. By the time of their origins, corporate capitalism was already well established. Radio and television were immediately under the control of a very few networks. “In recent years,” according to the journalists Juan Gonzalez and Joseph Torres, “commercial radio and television stations, and in increasing number of Internet news sites, have likewise become cloned subsidiaries of the big conglomerates, a half-dozen of which now exercise unparalleled influence over the dissemination of information.”[26] Four companies own 77% of all radio stations on the planet; four own 84% of all television networks, and eight own 98% of them; for consumer magazines, recorded music, and film entertainment, the top four and eight corporations own respectively, 77% and 78%, 98% and 100%, 91% and 100%.[27]

Source: http://www.businessinsider.com/these-6-corporations-control-90-of-the-media-in-america-2012-6

Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Ben Bagdikian writes that by 2004 just “Five global-dimension firms, operating with many of the characteristics of a cartel, own most of the newspapers, magazines, book publishers, motion picture studios, and radio and television stations in the United States.”[28] This dominance, he continues, gives each of these five conglomerates—Time Warner, The Walt Disney Company, Murdoch’s News Corporation, Viacom, and Bertelsmann—“and their leaders more communications power than exercised by any despot or dictatorship in history.”[29]

In the dispassionate tones of sober journalists, Gonzalez and Torres note that “This concentrated media ownership has become a major obstacle for those seeking to preserve a racially diverse and democratic system of news.”[30] Given the entwinement of corporations, business, and the military, the corporate media is not an independent institution allowed honest reporting on world events.[31] They are in bed with the other institutions. Or, as in the case of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, they are embedded with them.[32] According to McChesney and Nichols, the corporate pressures on reporters and editors “can be explicit… The effect is that the news is altered, unbeknownst to the public, in a manner it would never had been had the newsroom been independent and freestanding.”[33]

Embedded journalists in Baghdad (via BBC)

REFERENCES

[1] Shlain, L. (1998) The Alphabet versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image, Penguin/Compass, New York.; Weber, J. (2006) Strassburg, 1605: The Origins of the Newspaper in Europe, German History, v. 24(3), pp. 387-412.

[2] Rudd, C.A. (1979) Limits on the “Freed” Press of 18th- and 19th-Century Europe, Journalism Quarterly, v. 56, p. 521-530.; Barnhurst, K.G., and Nerone, J. (2009) Journalism History, pp. 17-28 in The Handbook of Journalism Studies, Wahl-Jorgensen, K. and Hanitzsch, T. (Editors). Routledge, New York.; McNair, B. (2009) Journalism and Democracy, pp. 237-249 in The Handbook of Journalism Studies, Wahl-Jorgensen, K. and Hanitzsch, T. (Editors). Routledge, New York.

[3] Croteau, D., and Hoynes, W. (2006:217) The Business of Media: Corporate Media and the Public Interest, Pine Forge Press, London.

[4] Examples from Holton, W. (2007) Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution, Hill and Wang, New York.

[5] Taylor, P.M. (2003) Munitions of the Mind: A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present day, Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK.

[6] The Economist (2011, July 7) Reinventing the Newspaper. Available at http://www.economist.com/node/18904178. Accessed April 15, 2012.

[7] Mensing, D. (2007, Spring) Online Revenue Business Model Has Changed Little Since 1996, Newspaper Research Journal, v. 28(2) 22-37.

[8] Croteau and Hoynes (2003:49); New York Times Alamanac 2011 (2010) Penguin Books, New York.. New Half of this went into newspapers, magazines, television and radio.

[9] Given that ad figures vary greatly based on source, the WPP (2011, December) GroupM forecasts 2012 global ad spending to increase 6.4% would supply the lower value, and extrapolating from U.S.A. data in NYT Almanac (2010) would give the upper value. Brower and Warren (1999) estimate $620 billion annually are spent by corporations on advertising (Brower, M. and Leon, W. (1999) The Consumer’s Guide to Effective Environmental Choices: Practical Advice from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Three Rivers Press, New York.)

[10] For example, see McChesney, R.W., and Nichols, J. (2010) The Death and Life of American Journalism: The Media Revolution that Will Begin the World Again. Nation Books, Philadelphia, PA.

[11] Stelter, B. (2012, April 20), No Place for Heated Opinions, New York Times.

[12] Stelter (2012).

[13] Chomsky, N. (1997, October) What Makes Mainstream Media Mainstream, Z Magazine.

[14] McChesney and Nichols (2010:41). This is not to say that there are not tens of thousands of journalists, many of them cited in these pages, who are committed to accurate and honest investigation and reporting. It is to say that it is easier to be successful in the field by writing excellent stories from a safe perspective.

[15] McChesney and Nichols (2010:17, 49); Gonzalez, J., and Torres, J. (2011) News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media. Verso, London.

[16] McChesney and Nichols (2010).

[17] Korten, D.C. (2001:148) When Corporations Rule the World, Second Edition, Kumarian Press, & Barrett-Koehler Publishers.

[18] Korten (2001:148).

[19] McChesney and Nichols (2010:49)

[20] McChesney and Nichols (2010:41), Gonzalez and Torres (2011:6), Columbia Journalism Review (2012, April 27) Who Owns What; Free Press (2012) Who Owns the Media? Freepress.net; Strauss, G., and Puente, M. (2012, March 1) Murdoch’s son steps down, USA Today.

[21] Gonzalez and Torres (2011:349-350).

[22] Gonzalez and Torres (2011:349-350).

[23] The New York Times Company Profile and Media Properties, Mediaowners.

[24] McManus (2009) The Commercialization of News, pp. 218-233 in in The Handbook of Journalism Studies, Wahl-Jorgensen, K. and Hanitzsch, T. (Editors). Routledge, New York.

[25] Gonzalez and Torres (2011:1-11).

[26] Gonzalez and Torres (2011:6).

[27] Croteau and Hoynes (2006:108).

[28] Bagdikian, B. (2004:3) The New Media Monopoly, Beacon, Boston, MA.

[29] Bagdikian (2004:3).

[30] Gonzalez and Torres (2011:6).

[31] McChesney and Nichols (2010:27-44).

[32] Cockburn, P. (2010, November 23) Embedded Journalism: A distorted view of war, The Independent: Ignatius, D. (2010, May 2) The Dangers of Embedded Journalism, In War and Politics, Washington Post. Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/30/AR2010043001100.html. Accessed May 6, 2012.

[33] McChesney and Nichols (2010:41).